Deacon James is a rambling bluesman straight from Georgia, a black man with troubles that he can’t escape, and music that won’t let him go. On a train to Arkham, he meets trouble—visions of nightmares, gaping mouths and grasping tendrils, and a madman who calls himself John Persons. According to the stranger, Deacon is carrying a seed in his head, a thing that will destroy the world if he lets it hatch.

The mad ravings chase Deacon to his next gig. His saxophone doesn’t call up his audience from their seats, it calls up monstrosities from across dimensions. As Deacon flees, chased by horrors and cultists, he stumbles upon a runaway girl, who is trying to escape the destiny awaiting her. Like Deacon, she carries something deep inside her, something twisted and dangerous. Together, they seek to leave Arkham, only to find the Thousand Young lurking in the woods.

The song in Deacon’s head is growing stronger, and soon he won’t be able to ignore it any more.

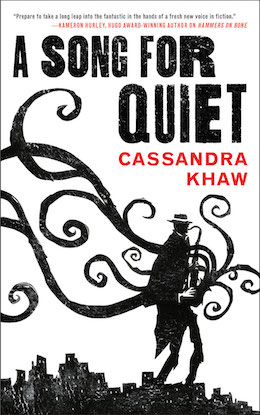

Cassandra Khaw returns with A Song for Quiet, a new standalone Persons Non Grata novella from the world of Hammers on Bone—available from Tor.com Publishing. And if you’re looking for more even more Lovecraftian tales, check out our Reimagining Lovecraft bundle, containing four full novellas: Khaw’s Hammers on Bone, Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Tom, Caitlín R. Kiernan’s Agents of Dreamland, and Kij Johnson’s The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe.

Chapter 1

The train rattles like teeth in a dead man’s skull as Deacon James sags against the window, hat pulled low over his eyes. Only a few share the wide, orange-lit carriage with him. A young Chinese family, the children knotted like kittens over the laps of the adults. An undertaker in his Sunday grim, starched collar and golden cufflinks on each sleeve. Two young black women trading gossip in rich contraltos.

Stutter. Jangle. Shove. Shriek. The train shudders on, singing a hymn of disrepair. Deacon looks up as civilization robs the night of its endlessness, finger painting globs of light and farmhouses across the countryside. In the distance, Arkham sits waiting near the dark mouth of the river, a rivulet of silver crawling to the sea. Deacon sighs and closes long fingers around the handle of his instrument case. The journey had been long, lonely, marked by grief for the dead and grief for himself. Every child knows they’re going to outlive their parents, but understanding is no opiate, can only mitigate. Knowledge can only propagate a trust that someday this will be okay.

But not yet, not yet.

What Deacon wishes for, more than anything else, is someone to tell him what to do in this period between hurting and healing, neither here nor there, the ache growing septic. What do you do when the funeral is over but your heart is still broken. When all the condolences have been spoken and the mourners have gone shuffling home, and you’re left to stare at the wall, so raw and empty that you don’t know if you’ll ever be whole again.

He breathes in, breathes out. Drags the musty heat of the carriage, too warm by half, into his bones before relaxing. One second, Deacon reminds himself. One minute. One hour. One day. One week at a time. You had to take each moment as it came, or you’d go mad from the yearning. He strokes his fingers across polished wood. In the back of his head, he feels the thump of music again: hot and wet and salty as a lover’s skin, begging for release.

But it’d be rude, wouldn’t it? Deacon traces the iron latches on his case and the places where the paint has faded and flaked, rubbed out by sweat and fingertips. A carriage of late-evening travelers, all hungry for home. Is he cold enough to interrupt their vigil?

The music twitches, eager and invasive. It wouldn’t be an imposition. It hardly could be. After all, Deacon can sing a bird from a tree, or that’s what they’ve told him, at least. It’d be good, whispers the melody, all sibilant. It’d be good for you and them.

“Why not?” Deacon says to no one in particular, scanning the quiet. His voice is steady, powerful, the bass of a Sunday pastor, booming from the deep well of his chest. A few slide lidded gazes at him, but no one speaks, too worn down by the road. Why not, croons the music in simpatico, a miasmic echo pressing down behind his right eye. Deacon knows, although he couldn’t begin to tell anyone how, that the pressure will alleviate if he plays, if he puts sentiment to sound. That he’d stop hurting—just for a little while.

And wouldn’t that be worth it?

Why not, Deacon thinks again, a little guilty, flipping open the case, the brass of his saxophone gleaming gold in the dim light of the train. The music in his skull grows louder, more insistent.

Dock Boggs’s “Oh, Death.” How about that? Something easy and sad, none too obtrusive. His father would have appreciated the irony. Deacon sets his lips to the mouthpiece and his fingers to the keys. Exhales.

But the sound that comes out is nothing so sweet, full of teeth instead. Like the song’s a dog that needs to eat, and he’s a bone in its grip. Like it’s hungry. The description jumps at Deacon, a crazed whine of a thought, before the song grabs him and devours him whole.

Raw, unevenly syncopated, the music’s a clatter of droning notes, looping into themselves, like a man mumbling a prayer. Briefly, Deacon wonders where he heard it, where he picked it up, because there is nothing in the music that tastes familiar. No trace of the blues, no ghost of folk music, not even the wine-drunk laughter of big-city jazz or the thunder of the gospel. Only a hard lump of yearning that snags like fishbones in his throat as he plays, plays, plays, improvisation after improvisation, frantically straining to wrench the bassline into familiar waters.

But it won’t relent. Instead, it drags him along, down, down, down, and under, deep into arpeggios for chords yet invented. And Deacon keeps playing to its tune, a man possessed, lungs jolting with every new refrain, even as the music mutates from a hypnotic adagio to a crashing, senseless avalanche of notes. Just sound and a fire that eats through him and yet, somehow, Deacon can

not

stop.

The lights shudder and swing, chains rattling.

And suddenly, there is nothing to stop, and it is over, and he is free, and Deacon is slumping into his seat, throat still foaming with the memory of the noise. His fingers burn. The skin is blistered and red. He knows in the morning they’ll swell with pus, become puffy and useless until he pricks the epidermis and bleeds the fluids away. Yet still, the song is there, throbbing like a hangover; softer now, sure, and quiet enough to ignore for a few hours, but still there, still waiting.

He wets his lips. Growing up, Deacon never had an interest in any drug except the kind you could write into an eighth-note shuffle rhythm, but he had friends who’d succumbed to the seduction of narcotics. They’d always tell him the same thing: that when they weren’t high, the longing would suck at them like a missing tooth. This new music felt like that.

Wrong.

Unclean.

Deacon shivers. All at once, he finds himself unable to shake the idea that there might be something burrowing through his skull, something unholy, voracious, a gleaming black-beetle appetite that’ll gobble him up and leave him none the wiser. So vivid is the image that it sends Deacon to his feet and away from his seat, breath shallowed into slivers, all sticking in the membrane of his mouth.

Air, he thinks. He needs air. Water. To be somewhere other than where he already is, to be on his feet moving, away from the horror that clings to the hem of his mind like the fingers of a childhood nightmare. And as Deacon stumbles through the carriage, drunk on terror, he thinks he can almost hear the music laugh.

* * *

This is what Deacon sees in the windows as he weaves between carriages.

One: The landscape, blurred into protean shapes. Jagged peaks thickening to walls, valleys fracturing into ravines, black pines melting into blasted plains. In the sky, the stars swarm, an infection of white, a thousand cataracted eyes. There is nothing human here, no vestige of man’s influence. Only night, only blackness.

Two: His face, reflected in the cold glass. Deacon looks thinner than he remembers, grief-gnawed, cheekbones picked clean of softness. His eyes are old from putting his pa into the soil and holding on to his mother as she cried bargains into his shoulder, anything to pluck the man she loves from the grave and put him back where he belongs, safe in her arms.

Three: Mouths, toothless, tongueless, opening in the windows, lesions on a leper’s back. Crowding the translucent panes until there is nothing but smacking lips, wet throats.

* * *

“What in Jesus—”

Deacon recoils from the window, nearly tripping into the half-opened door of a private cabin, an audacity that buys him a round of profanities from its occupants. He stammers an apology, but never finishes. A rangy cowboy stands, shoves him back into the corridor, a gesture that is wholly simian, swaggering arms and puffed-up xylophone chest under the drooping rim of his hat. Deacon stares at him, fingers tight around the handle of his case, body tense.

He was careless. He shouldn’t have been careless. He knows better than to be careless, but the carriages aren’t nearly as well demarcated as they could be, the paneling too unobtrusive, too coy about its purpose. Or maybe, maybe, Deacon thinks with a backward glance, he’d fucked up somehow, too caught up in a conversation with grief. He breathes in, sharp, air slithering between his teeth.

The man swills a word in his mouth, the syllables convulsing his face into a snarl, and Deacon can already hear it loud. After all, he’s heard it ten thousand times before, can read its coming in the upbeat alone. Sang, spat, or smoothed through the smile of an angel. Every variation of delivery, every style of excuse, every explanation for why it ain’t nothing but a word for people like him, innocent as you please. Yes, Deacon’s heard it all.

Thirty-five years on God’s green earth is more than enough time to write someone else’s hate into the roots of your pulse. So it isn’t until the man smiles, a dog’s long-toothed grin, that dread frissons down the long curve of the bluesman’s spine.

“You broke our whiskey bottle.”

“Didn’t mean to, sir.” Polite, poured smooth as caramel, like everything innocuous and sweet. It’s his best I don’t mean trouble, sir voice, whetted on too many late nights spent talking drunks out of bad decisions. The bottle in question rolls between them, unstoppered and undamaged. But Deacon says anyway: “Be happy to pay for the damages.”

A lie that will starve him, but hunger’s nothing that the bluesman isn’t acquainted with. And besides, there is a gig coming up. Small-time, sure, and half-driven by sentimentality—Deacon and his father had meant to play there before it’d all gone wrong.

Either way, money is money is money, and a cramped diner haunted by insomniacs is as good as any joint. If he’s lucky, they might even feed him too, stacks of buttermilk pancakes and too-crisp bacon, whatever detritus they have left over, all the meals sent back because they’re missing an ingredient, or have too much of another.

“I didn’t say I want payment.” His voice slaps Deacon from his reverie. The cowboy, reeking of red Arizona dust, lets his grin grow mean. “Did I say I want payment—” That word again, groaned like a sweetheart’s name. He slides his tongue over the vowels, slow, savoring its killing floor history, an entire opus of wrongs performed in the name of Jim Crow. “What did I say—” And the word is a rattlesnake-hiss this time, sliding between uneven teeth.

“You said I broke your whiskey bottle.”

The cowboy advances, a chink of spurs keeping rhythm. In the gloom behind him, Deacon sees silhouettes rise up: three leathery men, ropey as coyotes but nonetheless still broader than Deacon at the shoulder, their smiles like dirty little switchblades. And behind them—

A forest of mouths and lolling tongues, grinning like the Devil called home to supper; horns, teethed; tendrils dewed with eyes. The smell of sex-sweat, meltwater, black earth sweet with decay and mulch. Something takes a trembling fawn-legged step forward. A cut of light bands itself across a sunken chest crisscrossed with too many ribs.

The music rouses, a damp ache in his lungs.

This isn’t the time, he thinks, as the beat clanks out a hollow straight-four, like the shuffle of the train as it is swallowed by the mountain pass. The windows go black. Somewhere, a door opens and there’s a roar of noise: the chug-chug-clack of the train’s wheels and a cold, howling wind. Deacon glides backward, one long step; blinks again, eyes rheumy. Arpeggios twitch at his fingertips and though he tells himself no, his mind is already fingerpicking an elegy in distorted D minor.

The cowboy and his pack close in, hounds with a scent.

A door bangs shut.

“Please,” Deacon whispers, unsure who he is addressing or even what for, the syllable clutched like some wise woman’s favor, worthless in the blaze of day. Back pressed flat to the glass, he knows what’s next. Fists and boots and spurs, initialing themselves over his back; it’s easy to be vicious when you can call the law to heel. Deacon’s arms wrap tight about his instrument case as he shuts his eyes.

But the blows don’t come.

“Excuse me.”

Deacon opens his gaze to a stranger in the corridor, a silhouette sliced thin by the swinging lights. It moves jerkily, a marionette learning to walk without its strings, head tick-tocking through the approach. But when it shucks its fedora, the man—well dressed as any entrepreneur in a gray tweed coat and whiskey-sheen tie, shoes polished to an indulgent shine—does so with grace, one sleek motion to move hat over heart.

“Gents.” Light smears over gaunt cheekbones and a feral grin like something that had been left to starve. His voice is midwestern mild, neither deep nor shrill, a vehicle for thought and no more; his skin, bronze. The eyes are almost gold. “Hope I’m not intruding.”

The music skitters back, recedes into a throbbing behind Deacon’s eyeballs.

“Fuck. Off.” The cowboy spits, running blue eyes over the interloper, upper lip curled. “This ain’t your business.”

The newcomer sighs, just so, the smallest of noises, as he sloughs oiled black gloves. His hands belong to a boxer: thick, callused, knuckles bridged with scars. Crack. He pops the joints. “Real hard number, aren’t you? Sorry, chump. It’s definitely my business. See, Deacon James—”

Terror scalpels through the bluesman’s guts. He hadn’t said his name once since coming onboard. Not even to the conductor, who’d only smiled and nodded as he punched Deacon’s ticket, humming “Hard Luck Child” like a prayer for the working man.

“—he’s in possession of something I need. And consequently—” The man straightens, tucking his gloves into a breast pocket, taller than any of them by a head and a little more. His eyes are burnt honey and in the dim, they almost glow. “I need you palookas to step off before someone gets pinked.”

“Make us.”

The stranger grins.

Deacon’s eyes water as his universe rends in two. In one, he sees this: the cowboy lunging like an adder, a knife manifested in his gloved hand; the stranger twisting, still grinning, the other man’s forearm caught and bent with a snap, bone spalling through fabric; a scream unwinding from the cowboy’s throat, his nose crushed flat.

In another: a wound irising in the stranger’s palm, disgorging spined filaments of nerve and sinew; the cowboy’s arm consumed; a crack and crunch of bones breaking when the joint is twisted in half; a scream when a twist of meat carves the nose from the cowboy’s face.

In both worlds, both hemispheres of perhaps and might-be, the cowboy howls a second time, high and afraid, a babe in the black woods.

Deacon blinks and reality unifies into a place where one man moved faster than another; understood the anatomy of hurt better; knew where to apply pressure, where to push and dig and wrench. A mundane place, a simple place. Not a voracious cosmos where even flesh hungers, serrated and legion.

Moonlight slopes through the window, limning the corridor in cold. Daintily, the man in the tweed coat steps over the cowboy, the latter now heaped on the floor, groaning, long frame shriveled like a dead roach. Blood seeps in patterns from under his shuddering mass. “So. Any of you pikers want to join your pal here?”

Divested of their leader, the remaining men flee, leaving Deacon with that softly smiling stranger.

“Whatever you’re here for, I swear you’ve got the wrong cat. I’m neither a thief nor anybody’s outside man, sir. My records are clean. I’m paid up for this trip. Got my ticket right here.” Deacon inches back, instrument case pressed to his breast, the pounding behind his eyes excited to percussions, deep rolling thumps like the coming of war. He wets his mouth and tastes rust where the lip has somehow split. “Look, I’m just trying to get by, sir. Please. I don’t—”

The stranger cocks his head. A bird-like motion that he takes too far that sets his skull at a perfect ninety degrees. He’s listening to something. Listening and tapping out the meter with a gleaming shoe. Finally, he nods once, a line forming between his brow. “You haven’t done anything, pal. But you do have something—”

“The saxophone’s mine, fair and square. Said as much in my pa’s will.” His only relic of the man, outside of his crooked smile and strident voice, reflected in every mirrorward glance.

“—not the instrument. You can keep that.” There’s something about the man’s expression, the muscles palsied in places, the eyes lamplit. Something that comes together in a word like “inhuman.” “I need what’s in your head.”

“I don’t understand what you’re talking about.” The music crests, louder, louder; a layer of clicks running counterpoint to a hissing refrain, a television dialed to static. No melody as Deacon understands it, and somehow more potent for that reason. He almost doesn’t notice when the stranger leans in, no longer smiling, his skin drawn tight over his bones.

“Drop the act. You know exactly what I’m talking about. You’re listening to the bird right now.” He taps his temple with a finger. The train lurches, slows. Somewhere, the conductor’s hollering last stop, everyone get off. “Scratching at the inside of your skull, chirping away, remaking the world every time you sing for the primordial lady.”

“You’re crazy—” Yes. Yes. Yes. A single word like a record skipping, an oozing female voice stitched into the backbeat of a three-chord psalm to damnation.

“There’s something growing inside your head, champ. When she hatches, we’re all gonna dance on air.”

Yes. Yes. Yes. Yes. Yessss.

And just for a minute, reality unlatches, long enough and far enough that Deacon can look through it and bear witness to the stranger’s lurking truth: a teeming life curled inside the arteries of the man, wearing his skin like a suit. Not as much a thing as it is the glimmering idea of a thing, worming hooks through the supine brain.

It takes a fistful of heartbeats before Deacon realizes he’s screaming, screaming as though stopping has long since ceased to be an option. The music in his skull wails, furious, and all the while Deacon’s backing away, stumbling over his own feet. A door behind the stranger bangs open, admitting a conductor, scraggly and sunken-eyed from being dug from his sleep.

“Hey, what’s goin’ on here? You know you colored people ain’t allow in this carriage!”

The stranger turns and Deacon runs.

Excerpted from A Song For Quiet, copyright © 2017 by Cassandra Khaw.

This excerpt originally appeared in July 2017.